Today in Edworking News we want to talk about Andy Warhol’s lost Amiga art found

After 39 years, Andy Warhol’s lost Amiga art has been found. And it’s for sale. Details of the reemergence help to shed light on an earlier discovery from about a decade ago. And those details come from the very person who taught Andy Warhol how to use a computer. In this blog post, I’ll put these discoveries in context, and offer some thoughts from both an art teacher and a sales engineer.

The lost Andy Warhol image of Debbie Harry

The lost Andy Warhol image of Debbie Harry

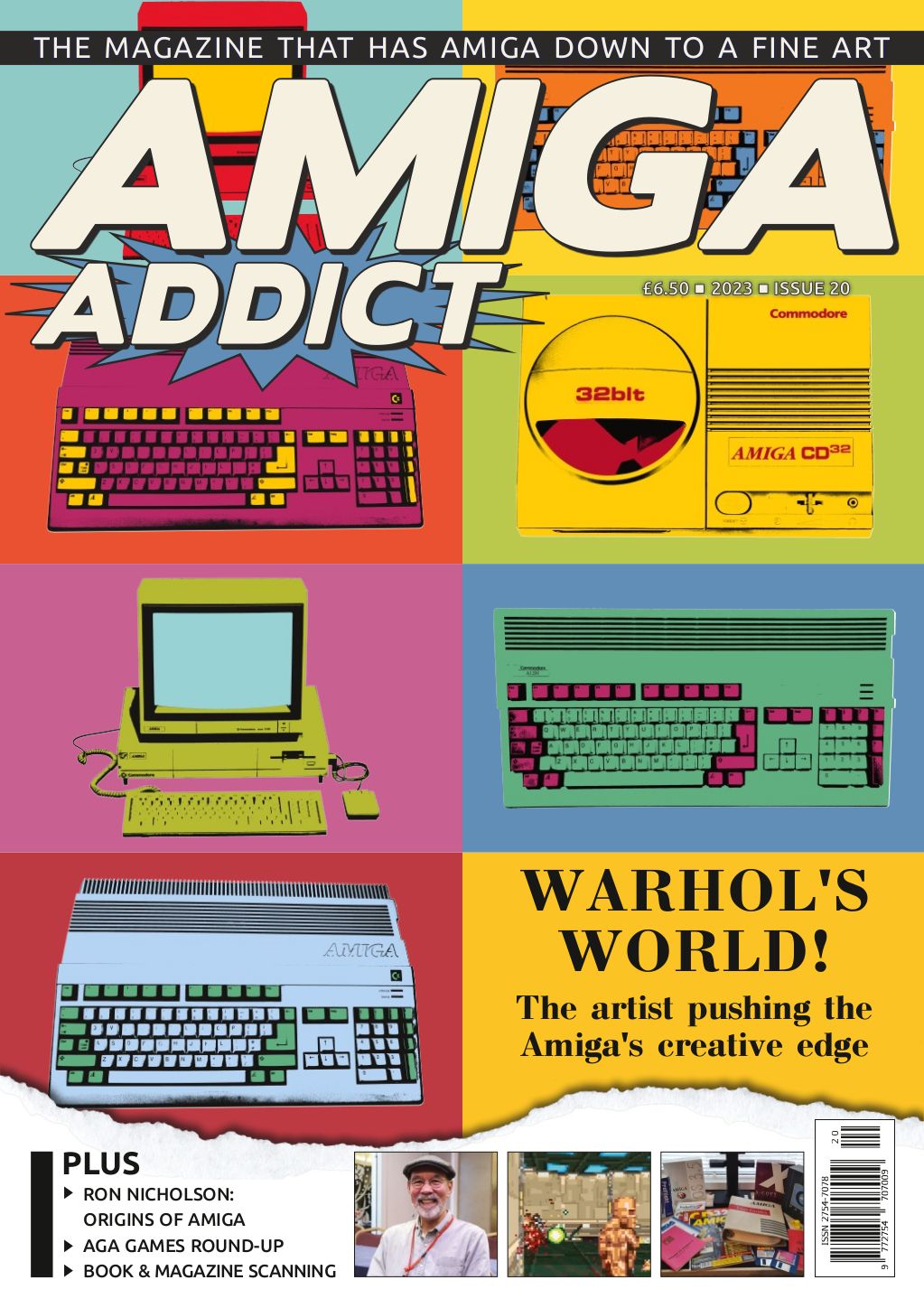

Commodore famously commissioned Andy Warhol to demonstrate the artistic capabilities of its new Amiga 1000 computer in 1985. As part of his demonstration, Warhol created some digital art images, including a self-portrait of himself sitting in front of the computer, which in turn was displaying the self-portrait. Another image he created was a famous portrait of Debbie Harry, the photogenic lead singer of the New Wave band Blondie.

In recounting the event, Debbie Harry said in her autobiography that she had a copy of the images from the event, and as far as she knew, only one other person had a copy. She did not identify the other person.

The unnamed other person

The unnamed other person

In July 2024, former Commodore engineer Jeff Bruette came forward and said he owns a print of the image Andy Warhol created at the event, and a signed floppy disk containing eight images that Andy Warhol created that day. He said he’s had them on display in his home for about 39 years. Some of the accounts of the Warhol art resurfacing describe Bruette as a technician, and although that was essentially the role he was serving at the event, he was much more than a technician. He was a long-time Commodore employee, and he programmed two popular early Commodore 64 games that Commodore distributed commercially, Gorf and Wizard of Wor. Bruette also acted as the product manager of the graphics software Warhol used. He was more than a technician to Andy Warhol as well. He was the one who taught Andy Warhol how to use an Amiga. For that matter, he probably taught Andy Warhol almost everything he knew about computers in general, not just Amigas.

Andy Warhol’s demonstration Amiga art

Andy Warhol’s demonstration Amiga art

The digital images Andy Warhol created are rudimentary by today’s standards, and in some ways, perhaps less ambitious than some of the thumbnails I create for my blog posts. But this was 39 years ago, and I have much better tools than he did. The maximum resolution he had to work with was 640 pixels in one direction and 400 pixels the other direction. And while he had 4,096 colors to choose from, he could only use 32 of them at a time. He had a digital camera available to him, but it wasn’t a digital camera in any modern sense. It was really best suited to taking monochromatic images. To a casual viewer, they look like low-resolution images with a very limited number of colors, and it’s not completely unfair to say they bear some resemblance to something my kids would have created in Microsoft Paint when they were little.

Description: One of Andy Warhol's digital artworks created using the Amiga 1000.

An art teacher’s impression

An art teacher’s impression

But when I showed the images to my wife, a former high school art teacher, the first thing she noticed was his choice of colors. He deliberately chose colors that contrasted with each other, and the other colors he used were colors you would get from mixing two or more of the other colors he used. Rule number one of painting, she said, is to never use black or brown, but make your own from the other colors you’re using. Warhol’s images contain odd shades that result from mixing other colors in the image together. When you look at Andy Warhol paintings, his style suited these specific tools. He often worked from photographs, creating stark images containing bold flood fills with only a few colors. Sometimes he would cut up photographs, or have someone else cut up the photographs, then he would arrange the pieces and then paint what he saw. With the Amiga, he could do all of this digitally. So the choice of Andy Warhol to demonstrate how to use the machine was a brilliant idea. This computer with advanced graphics capabilities for its time, and the ability to multitask and switch between different tools so he could cut up and resize images and then paste the result into the image he was working on couldn’t have suited him any better if he’d designed it himself. Problem was, he didn’t know how to use a computer.

Andy Warhol’s body language

Andy Warhol’s body language

In all of the photographs I have seen of Andy Warhol with an Amiga, I noticed something. He is never, ever holding the mouse the way I would hold it. He has a death grip on the sides with his thumb on one side and his index and pinky finger on the other. And then he has his pointer and middle fingers curled up, as far away from the two mouse buttons and he can possibly get them while still being able to maintain the death grip on the mouse body. It betrays a fear of accidentally clicking either of the mouse buttons and another fear of accidentally dropping the mouse, or perhaps even accidentally moving the mouse.

Warhol’s lament

Warhol’s lament

I read somewhere that Andy Warhol didn’t think he was very good at demonstrating how to use the computer, and he wished he could get good at it, because it seemed like a really good way to make money. I asked Jeff Bruette about that, and he said that was consistent with his experience with Warhol. “He saw the things that [AmigaWorld magazine’s art director] was able to create and how I could fluidly click the tools, colors, and menus to create things. He was completely inexperienced with computers and struggled with the process,” Bruette said. “In fact, we would go through things together in the morning. After breaking for lunch he’d need a refresher on the difference between the right and left mouse buttons. True story,” he added.

For those unfamiliar with the Amiga, the left mouse button works like the left mouse button in Windows and other operating systems. The right mouse button activated the pull-down menus at the top of the screen. Conceptually, it was similar to context menus in today’s operating systems.

A modern sales engineer’s critique

A modern sales engineer’s critique

Warhol’s results in creating his computer art were inconsistent. The famous image of Debbie Harry was not the result of the live demonstration. It came from a rehearsal earlier in the day. When he tried to recreate the image live with an audience, the result didn’t look like an Andy Warhol painting. Bruette shared the image in a private group, so I don’t feel like I am at liberty to share it, but I’ll share the story. The lighting conditions were different during the event than they had been at rehearsal, so the photo he started with had different contrast. The flood fill to the right of Debbie Harry went fine. When he filled her hair, it was fine on the right side of the image, but not so good on the left. And exactly zero of his other flood fills did what he intended. Without the level of undo that modern paint programs have, he didn’t have an easy way to correct even that first mistake. His efforts to correct it just ended up blowing out her face. Instead of looking like an Andy Warhol painting of Debbie Harry, it looked like what you’d get if you told an impressionist to paint a woman with long hair.

In my day job, one of my responsibilities happens to be giving product demos. I’ve experienced demos where one mistake compounds the next. You learn to roll with it, but it takes practice. When Commodore released the video of the event, they spliced in the image from the rehearsal session.

What about flood fills?

What about flood fills?

I’ve heard several stories from other Commodore engineers about how the flood fill function in the software they were using would crash the machine. I’m pretty sure those stories have even ended up in books about Commodore. Bruette said the flood fills were working in the versions of the software Warhol had, and that’s pretty clear even from the images in Warhol’s estate. To create Warhol-style digital art, you need to be able to capture an image from a camera, resize it, copy and paste it, select your colors, and do flood fills on it. In a pinch you can get by without resizing and copying and pasting, but not having flood fills would be a showstopper.

How the earlier discovery relates

How the earlier discovery relates

In 2014, a series of images was recovered from disks found in Andy Warhol’s estate. His personal effects included two pre-production Amiga computers and a collection of disks containing not just the files he created, but also the software he used to create those images, including a previously undiscovered early version of the operating system. In a blog post I wrote at the time, I speculated that the images were the result of him trying to learn how to use the computer. Looking at the images again, I think they were more than that. He was experimenting with techniques. One of the images appears to be a photograph of himself where he clicked around with the fill function. But when you look at the image more closely, you can see where he had three different images of himself of differing sizes, and he superimposed the three, then he started messing around with fills.

Insights into how (and what) Warhol learned

Insights into how (and what) Warhol learned

I can almost see and hear Jeff Bruette explaining the capabilities of the computer to Andy Warhol, and then him walking through what Bruette had just described, trying to create in his own style using what he had just learned. That’s because I had to do something similar. The discomfort level in the photographs of Andy Warhol with the computer remind me of something. I was in the odd position of teaching my own teachers about computers from the time I was a teenager into my mid-20s. Many of them had the same level of discomfort with the mouse. I would fire up Solitaire and have them play that to get used to clicking and dragging. Bruette didn’t have that luxury when tutoring Warhol.

The lost opportunity

The lost opportunity

I always wished Commodore had pursued the Andy Warhol connection further. Now I understand why it didn’t happen. I don’t think Commodore marketing recognized the opportunity, but I also don’t think Andy Warhol was comfortable with it. It wasn’t the same as sitting William Shatner down in front of a VIC-20 with a simulated screen on the TV and showing him how to position his hands so it looked like he was typing and showing him where the cameras were so he could make sure he was looking at the camera while he was smiling. He was trying to do it right, he struggled to do it live, and he gave up. He was trying to be a modern-day sales engineer, but without the benefit of the professional training that I received. I also had at least five years of professional experience with the product I was demonstrating before gaining the title of sales engineer. I also sometimes had to give product demos at another company, a company whose software was not as far along, and where I had about the same level of experience and as Andy Warhol did, and let’s just say that didn’t go as well.

A possible workaround

A possible workaround

But they had options. They could have done a Shatner-like maneuver in print advertising, having Warhol mime in front of the computer, with a copy of the image on screen but the mouse unplugged, just to make it look like he was producing it live. And then they could have added some text about how this new computer is the first one ever that works the way Andy Warhol does.

At any rate, I think it’s fantastic that the images Andy Warhol created on that day survive, we now know where the copy is, and the person who preserved them for 39 years will have a chance to get them into the hands of someone who will enjoy them, and use the proceeds to fund his retirement. That sounds like a win all around to me, and it closes the loop on some details of Andy Warhol’s involvement with the Amiga computer.

Description: Andy Warhol demonstrating the Amiga 1000.

Remember these 3 key ideas for your startup:

Remember these 3 key ideas for your startup:

- Embrace Technological Evolution: Just like Warhol experimented with the Amiga, startups should not shy away from exploring new technologies. This can open up new avenues for creativity and efficiency. For instance, integrating AI tools can significantly enhance productivity and innovation.

- Learn from Mistakes: Warhol’s struggle with live demonstrations teaches us the importance of practice and preparation. Startups should adopt a culture of learning from failures and continuously improving their processes. This iterative approach can lead to more robust and reliable outcomes.

- Leverage Marketing Opportunities: Warhol’s association with the Amiga was a missed marketing opportunity. Startups should capitalize on unique partnerships and endorsements to boost their brand visibility. Effective marketing can significantly enhance a startup's reach and impact.

Edworking is the best and smartest decision for SMEs and startups to be more productive. Edworking is a FREE superapp of productivity that includes all you need for work powered by AI in the same superapp, connecting Task Management, Docs, Chat, Videocall, and File Management. Save money today by not paying for Slack, Trello, Dropbox, Zoom, and Notion.

David Farquhar is a computer security professional, entrepreneur, and author. He started his career as a part-time computer technician in 1994, worked his way up to system administrator by 1997, and has specialized in vulnerability management since 2013. He invests in real estate on the side and his hobbies include O gauge trains, baseball cards, and retro computers and video games. A University of Missouri graduate, he holds CISSP and Security+ certifications. He lives in St. Louis with his family.

For more details, see the original source.